Share this Post

ROLLS-ROYCE ‘MAKERS OF THE MARQUE’: CLAUDE GOODMAN JOHNSON

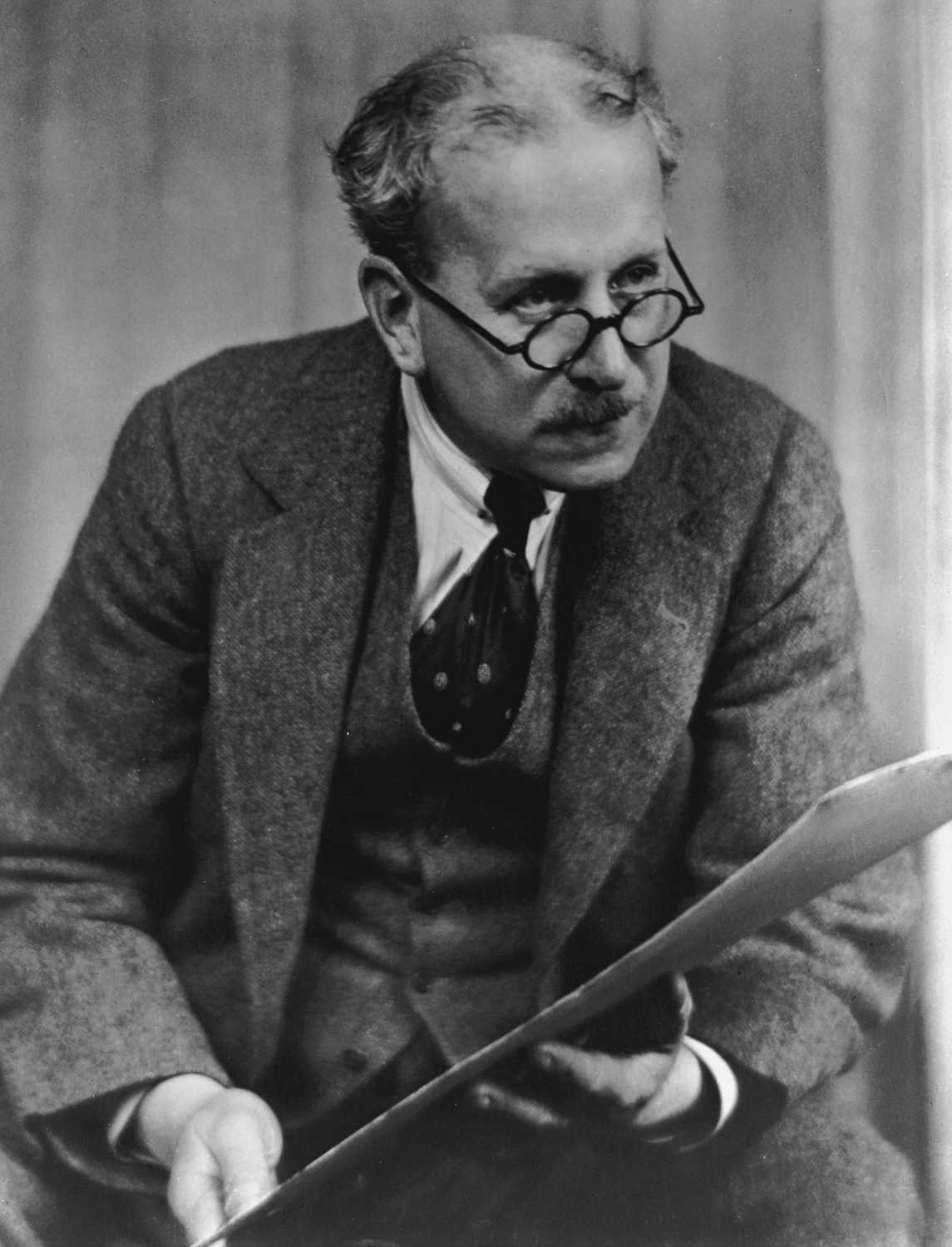

CLAUDE GOODMAN JOHNSON: 24 OCTOBER 1864 - 11 APRIL 1926

- A brief overview of the life and career of Claude Goodman Johnson, born 24 October 1864

- The self-styled ‘hyphen in Rolls-Royce’ and the marque’s first Commercial Managing Director

- A larger-than-life character, Henry Royce once said of him, “He was the captain; we were only the crew”

- Indelibly shaped the marque’s development and legacy

- Dedicated to upholding Rolls-Royce’s status as ‘the best car in the world’

- Sixth in a series profiling the principal characters in the Rolls-Royce Motor Cars’ story

- Published in recognition of the marque’s 120th anniversary in 2024

“Claude Johnson is celebrated by posterity as ‘the hyphen in

Rolls-Royce’; it is typical of the man that this is a title he gave

himself. But if anything, it understates the importance and

influence of ‘CJ’, as he was universally known, in the marque’s

first two decades and beyond. A natural showman with a genius for

generating publicity – for himself, as well as the company – his

ideas, energy and personality matched his imposing physical stature.

He brought an extraordinary mix of skills, talents, experience and

personal qualities to his role as the company’s first Commercial

Managing Director: a truly fascinating, larger-than-life character

with a colourful background who achieved remarkable things.”

Andrew Ball, Head of Corporate Relations and Heritage,

Rolls-Royce Motor Cars

Claude Goodman Johnson – known to all simply as ‘CJ’

– was born in Buckinghamshire on 24 October 1864, one of seven children.

From London’s St Paul’s School, Claude progressed to the Royal

College of Art. Here, he met Sir Philip Cunliffe-Owen, Deputy General

Superintendent of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria &

Albert Museum), where Claude’s father worked. Through him, CJ secured

his first job, as a clerk at the Imperial Institute (now Imperial

College London). There, he was put to work arranging exhibitions. His

debut effort, the Fisheries Exhibition, was described in W. J. Oldham’s book The

Hyphen in Rolls-Royce as the ‘fashionable haunt of London for

the summer of 1883’. He followed this triumph with events dedicated

to Health in 1884 and Inventions the following year;

by the time his Colonial and Indian Exhibition opened in

1886, CJ was managing a workforce of around 200.

But if his professional life was a model of sober industry, CJ’s

personal circumstances were already somewhat more colourful. Soon

after starting work at the Institute, he eloped with his girlfriend,

Fanny Mary Morrison, much to the distress of both sets of parents.

They had eight children, but tragically only the seventh child, Betty,

survived. Eventually, the marriage failed, whereupon CJ married his

long-time mistress, whom he always called ‘Mrs. Wiggs’; they had a

daughter known as Tink.

ON WITH THE SHOW

His private life had no

discernible effect on CJ’s career trajectory. In 1895, the leading

scientific author and road transport pioneer, Sir David Salomons,

organised England’s first ‘Motor Exhibition’ at his home in Tunbridge

Wells. The event proved only moderately successful, but caught the eye

of the Prince of Wales, an enthusiast for the ‘new’ motor cars. His

Royal Highness was keen to try a similar exhibition – and where better

than at the Imperial Institute, which he had long championed, and who

better to arrange it than the Chief Clerk, Claude Johnson?

That 1896 event, rather quaintly entitled Motors and their

Appliances, proved a turning point for CJ. By July 1897, a group

of enthusiasts had founded the Automobile Club of Great Britain &

Ireland (later the Royal Automobile Club, or RAC), but were still

looking for a full-time Secretary. Aware of his success in organising

the Imperial Institute exhibition, they offered CJ the job, which he

eagerly accepted.

His talents for organisation and promotion made him perfect for

the role. Under his auspices, the Club held numerous motoring events

for its members, including the 1000 Mile Trial run during

April and May 1900, and won by a certain Charles Stewart Rolls in his

Parisian-made 12 H.P. Panhard.

IN GOOD COMPANY

By 1903, CJ had almost

single-handedly built the Club’s membership to around 2,000. But his

restless mind was ready for a change, and when Club member Paris

Singer, son of sewing machine magnate Isaac Singer, offered him a job

with his City & Suburban Electric Car Company, CJ jumped

at it. This, too, was only a stepping stone to what would become his

life’s work. After just a few months with Singer, he joined another

Club member in his fledgling car-sales business, a certain C.S. Rolls

& Co., thus changing the course of history.

As business partners, the two men were ideally matched. The

urbane, well-connected, Cambridge-educated engineer Rolls looked after

the technical side of things (and dealt with the nobility), while CJ

handled publicity and sales to less exalted patrons.

The company flourished, but Rolls was desperate to find a

British-made motor car as good as the Continental models they were

selling. In 1904 he found it, in a new 10 H.P. car made by Henry

Royce. Following their historic first meeting in Manchester on 4 May,

Rolls returned to London and informed CJ he had agreed to sell every

car Royce could make under a new name, Rolls-Royce. CJ was instantly

captivated by the project, and when the Rolls-Royce company was

formally established in 1906, he assumed the role of Commercial

Managing Director.

SUCCESS BREEDS SUCCESS

CJ’s talent and

enthusiasm for publicity stunts had found its perfect outlet. In 1906,

Rolls-Royce won the Scottish Reliability Trials with a 30 H.P. motor

car. At CJ’s urging, Royce developed a larger, more powerful model,

the 40/50 H.P. capable of carrying larger bodywork. In an inspired

move, CJ dubbed the 12th example, with its silver-plated brightwork

and silver paint, ‘The Silver Ghost’ and entered it in the 1907 event,

which it won convincingly. A lesser person might have been satisfied,

but not CJ. To underline the motor car’s reliability, he immediately

arranged for it to participate in a ‘non-stop’ run – a drive without

an involuntary stop on the road, apart from punctures, during a set

period in the day. Travelling back and forth between London and

Edinburgh (except on Sundays), they amassed nearly 15,000 miles and

set a new world endurance record. Characteristically, CJ drove the

first 4,000 miles himself, yet found time every day to send a postcard

to his four-year-old daughter.

Less arduous but equally noteworthy PR efforts followed: placing

a brimming glass of water on a running engine without spilling a drop

and balancing a coin on the edge of the radiator cap without it

falling over. CJ also wrote and published a successful series of

guidebooks with Lord John Montagu entitled ‘Roads Made Easy’, which

included the charming direction ‘FTW’, meaning ‘follow the telegraph

wire by the roadside’.

It was through Montagu that CJ met the illustrator and sculptor

Charles Sykes. Rightly concerned that the fad among motor car owners

for fitting comical mascots to their radiator caps was spoiling the

cars’ classical lines, he commissioned Sykes to design an official

one. What we know today as the Spirit of Ecstasy was unveiled in 1911,

and it remains one of CJ’s most important and enduring legacies. Still

adorning the prow of Rolls-Royce motor cars to this day, CJ’s

commission has gone on to become the marque’s timeless muse and an

inspiration for countless masterpieces, including its recent Phantom

Scintilla Private Collection.

A FRIEND INDEED

It would be easy to assume that

the ebullient, outgoing CJ would have little in common with the

serious, rather austere engineer Royce. In fact, the two were close

friends, respectful of each other’s integrity; Royce’s unending desire

to design the best motor car possible was perfectly complemented by

CJ’s ability to keep the Rolls-Royce name firmly in the public

consciousness, and the operation running smoothly.

Indeed, it’s little exaggeration to say that CJ saved Royce’s life.

By 1911, years of overwork and poor diet had taken a severe toll on

Royce’s health, and he fell seriously ill; after an operation, he was

given just three months to live. The Derby factory was too stressful

an environment, so CJ found Royce a house, at Crowborough in East Sussex.

On a convalescent trip to the South of France – travelling in

CJ’s magnificent green-and-cream Barker-bodied limousine he’d

named The Charmer – they stopped at CJ’s holiday home,

Villa Jaune, at Le Canadel. Royce liked the place and said

he could happily spend the winter months working from there. CJ

immediately bought a nearby plot of land and built three houses,

designed by Royce. Villa Mimosa was for Henry himself,

while Le Bureau served as a design studio, and Le

Rossignol – ‘the nightingale’ – was the house in which the

designers lived. It was very important to Royce that the designers

were close to him, so that they were able to quickly bring their

respective visions to reality. Royce divided his time between England

and France until his death in 1933.

CHANGING TIMES

CJ’s own capacity for work was

undiminished. In 1912, he opened a sales showroom in Paris, decorated

in Adam style with Louis XVI-style furniture. That same year, Silver

Ghost owner James Radley started the gruelling Austrian Alpine Trial,

but failed to finish. Outraged, CJ vowed to avenge this humiliation,

and in 1913 entered a ‘works’ team of three cars (plus Radley as a

privateer) with redesigned, four-speed gearboxes. The cars swept the

board in what would be the last competitive event to be arranged by

CJ. During this period, CJ also introduced the first three-year

guarantee on Rolls-Royce motor cars and set up a pension scheme for

the workforce.

From 1914 to 1918, Rolls-Royce focused exclusively on aero

engine production – something CJ had insisted upon for both commercial

and patriotic reasons. But even before hostilities ceased, he foresaw

that large, complex and expensive motor cars like Silver Ghost would

have limited appeal in a straitened, post-war world. He therefore

proposed a smaller model that would be suitable for owner-drivers,

which Royce duly delivered with the new 20 H.P. Cannily, CJ spotted

that under the new Road Tax, charged at £1.00 per RAC-rated unit of

horsepower, the Silver Ghost would attract a tax of £47.00 a year, but

the new 20 H.P. only £20.00.

CJ made two further lasting major contributions to Rolls-Royce

motor cars. First, when Royce proposed to abandon the traditional

Pantheon radiator design for something more streamlined, CJ

successfully persuaded him otherwise. Second, when Silver Ghost’s

replacement model was ready in 1925, CJ named it after a pair of

former Trials cars that were both known as Silver Phantom. He called

this model New Phantom; eight generations later, what would become the

most storied nameplate in the marque’s history celebrates its own

centenary in 2025.

“HE WAS THE CAPTAIN; WE WERE ONLY THE CREW.”

On

6 April 1926, CJ went to his Conduit Street office as usual, despite

having felt unwell and losing a noticeable amount of weight for some

time. The following day he felt worse, but forced himself to attend

his niece’s wedding, where he collapsed. He was driven home by his

eldest daughter Betty; on the way, he told her that he felt he would

not pull through, and that he wanted neither fuss nor flowers at his

funeral. His death on Sunday 11 April was reported by national

newspapers and the BBC, reflecting his high public profile and immense

importance to Rolls-Royce. Royce was deeply distressed at his old

friend’s death, saying: “He was the captain; we were only the crew.”

For all his professional elan and showmanship, CJ was personally

modest and highly scrupulous. He never held shares in the company,

lest he should be accused of feathering his own nest, nor did he own a

Rolls-Royce motor car himself, always using a company Trials car

instead. When he was offered a knighthood for Rolls-Royce’s

contribution to the war effort, he declined it, saying it should be

awarded to Royce (who received only an OBE). He was forever reluctant

to accept praise, always directing it towards his co-workers.

A true bon viveur, CJ enjoyed the best he could afford for

himself, his family and close friends. His daughter Tink described him

as: “A big man in every way: 6’2”, equally broad and well-proportioned

with large and most beautiful hands. His size epitomised his ideas,

ideals and generosity, his outlook and enthusiasm. A wonderful father,

always very well dressed.” But perhaps the best summary of this

remarkable man came from his close friend, the English portrait artist

Ambrose McEvoy: “A wise and kindly giant”.